Vampire Survivors and Jackson Pollock

The pleasure of diving into chaos. #painting #videogame

Welcome back to Artcade, the secret passage that spits us out inside other people’s obsessions. Sometimes they are wall-sized paintings, sometimes they are low-resolution screens; in both cases your brain is close to boiling and still keeps saying “more, more.”

We keep telling ourselves we are exposed to too many emails, too many notifications, too much information, too much content (and too many lists). Yet, never satisfied, the moment we get a free hour we definitely do not sit and stare at a blank wall. We sit in front of something that promises to fill our head a little more: a TV show, a social feed, a game (or a list). It’s a dependency, and if we cannot beat it we should at least choose carefully what we cram into our brains. If you’re reading this, take it from your bartender (who’s obviously biased): you’ve got good taste. Enjoy the read!

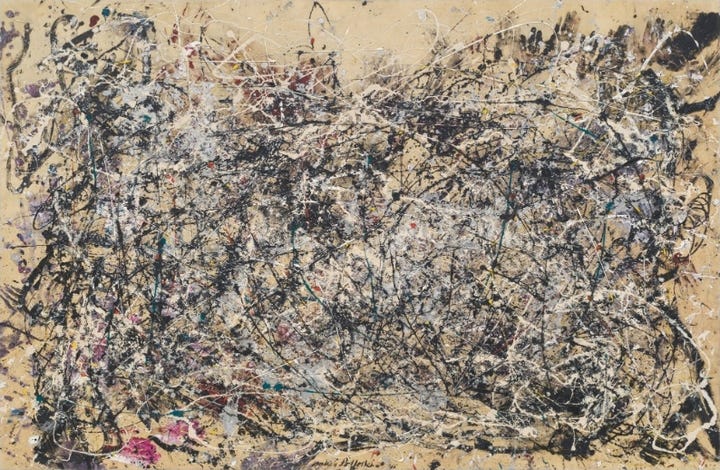

Jackson Pollock (1948) Number 1A [Painting] [Abstract Expressionism] [Oil and enamel on canvas] [172.7 × 264.2 cm (68 in × 8 ft 8 in)] MoMA, New York

Let’s try to imagine Number 1A without the résumé: no “masterpiece of Abstract Expressionism”, no exhibition space at MoMA in New York.

Or let’s try to forget that Number 17A was purchased for 200 million dollars.

Jackson Pollock (1948) Number 17A [Painting] [Abstract Expressionism] [Oil on fiberboard] [112 × 86.5 cm (44 in × 34.1 in)] Private collection of Kenneth C. Griffin

If we just look at them, they are only a web of lines, stains, drops, as if a doodle had been copied over and over until it occupied every inch of the canvas. This is usually the moment when someone snaps and goes for the classic “I could have done that too.”

In reality Pollock dismantled the idea of a painting so much that for a while he replaced titles with numbers: Number 1, Number 10, Number 29… different versions of the same file. The canvas is just a rectangle laid on the floor, with a man walking around it like he is performing some kind of strange ritual.

Pollock is not sitting at an easel refining details. He walks, drips, throws, lets paint run out of the can. The canvas is a floor where something happens and the result no longer has a center, your eye wanders because every point seems as important as the others. Goodbye perspective, figures, classical representation. Behind the apparent mess there is a system of repeated gestures that he controls just enough to never paint the same canvas twice.

Jackson Pollock (1952) Blue Poles [Painting] [Abstract Expressionism] [Enamel and paint on canvas] [212.1 × 488.9 cm (83.5 in × 192.5 in)] National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

In 1952 Pollock paints Blue Poles. On top of his usual whirl of lines and splashes he plants eight dark blue columns that cut across the canvas. Whether you see utility poles in the middle of a storm or characters trying to hold back a party that has clearly got out of hand does not really matter. When the National Gallery of Australia bought the painting in the Seventies for one million three hundred thousand dollars, the country erupted into exactly the kind of controversy newspapers love. Decades later the painting has become one of the museum’s symbols. Chaos, at some point, always wins.

The secret of Jackson Pollock’s success lies in the way he paints, which is similar to the way many of us play. Pollock steps into the canvas, inhabits it, repeats the same movements until he reaches that threshold where the painting is done. One gesture too many and he ruins everything, one gesture too few and it feels unfinished. Every canvas is the residue of a performance that plays out the relationship between control and loss of control. In the end the painter stops, and we stop with him. Motionless, watching the chaos.

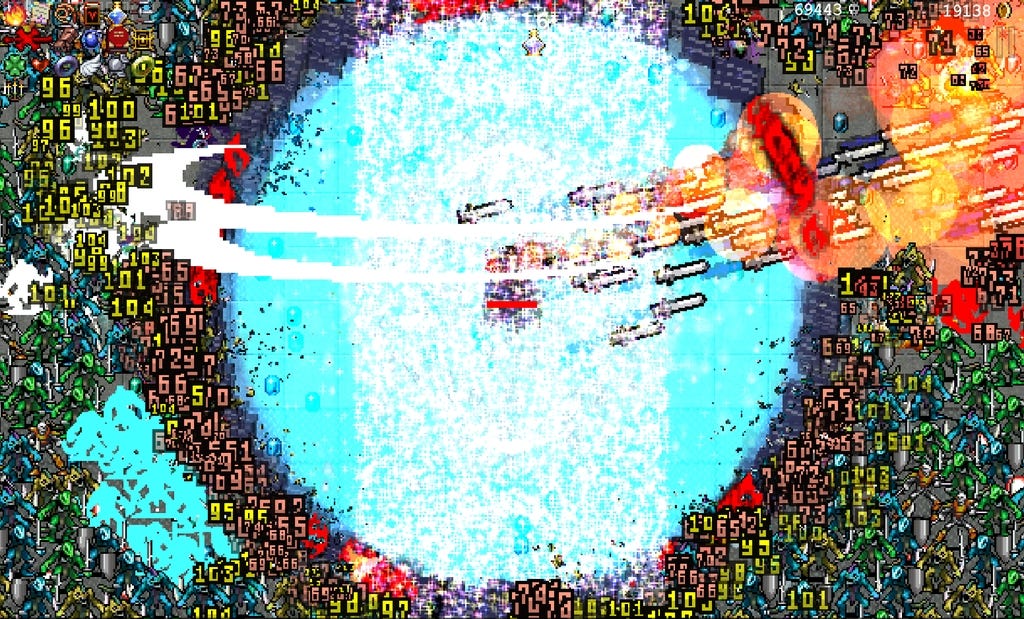

Look at the empty screen at the beginning of a Vampire Survivors run. Flat green, a few bats, a couple of things on the ground. It looks like the base layer of a Nineties JRPG left halfway through production. In the middle there is a tiny little guy who basically does nothing except walk. It is the phase where the game makes you feel like a hopeless nobody at the center of a gigantic field, when in reality you are a still-sealed can of paint.

Vampire Survivors is extremely simple: you control movement, the weapons fire on their own. At first it is so basic that it feels disorienting. You move, collect gems, pick an upgrade, repeat.

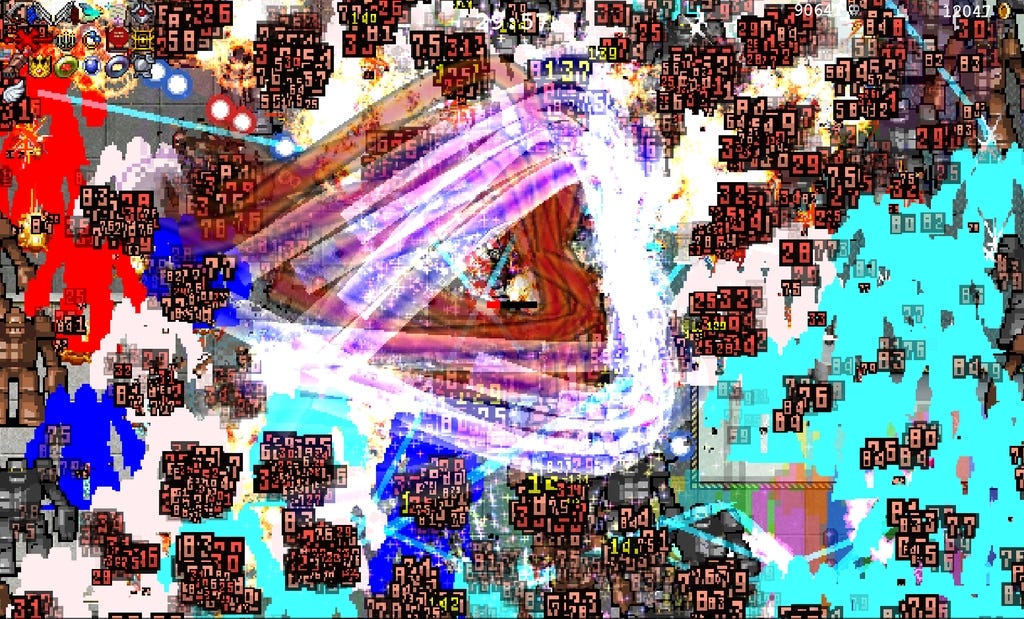

Each choice adds a new “brushstroke” to the way you occupy space. Pick the knife and your character starts spitting little triangles that whistle horizontally. Pick the Bible and here comes a circle of damage orbiting around you. Grab the whip, the cat, the laser, lightning, the rain of crosses. Everything fills the screen with a different kind of stroke.

Once you get past twenty, thirty minutes, the same thing happens that you get in front of a Pollock: chaos takes over the canvas. The protagonist is buried under an avalanche of damage numbers, enemies stop being individuals and turn into patterns, effects close every gap. The character you are steering becomes less important and the weapons spin around you like layers of enamel paint.

The interesting thing is that none of this is actually random. Under the visual storm there is a very precise machine: probability tables, spawn patterns, synergies between items. If you repeat the same build and move roughly the same way, the screen will produce a composition similar to the previous run. Change a single upgrade and suddenly the rhythm of the numbers, the dominant colors, even the shape of the enemy masses changes. It is exactly the logic of Pollock’s paintings: behind the chaos there is a regularity that your brain recognizes even if it doesn’t really understand it.

Vampire Survivors is, in practice, a generator of fleeting abstract paintings. Every run is a half-hour performance where your minimal input (moving a character) gets amplified by a cascade of visual consequences. Only two things can happen during a run: you die, as per contract, or you end up creating your own personal Pollock. Once you reach that level the game almost stops existing. You stand still and stop touching anything. The same effect as a Pollock painting that has reached its perfect cooking point. Chaos has taken shape and there is nothing left for us to do except watch.

poncle [Luca Galante] (2022) Vampire Survivors [Video game] [Roguelike, Bullet heaven] [15 hours] (iOs) [Windows, macOS, Xbox One/Series X/S, Nintendo Switch, Android, PlayStation 4/5] poncle

Information Desk:

The story of Luca Galante, the creator of Vampire Survivors, is one of those stories that make the masses dream. From McDonald’s to international awards.

Hard to believe, but Blue Poles really is considered “the most controversial painting in Australian history.”

Ken Griffin, the guy who bought Number 17A for 200 million, also tried to buy Blue Poles, because that one is actually his favorite Pollock.

My last two coins

The old-school look of Vampire Survivors seems tailor-made not to be taken seriously. At first glance Pollock’s abstract paintings look like evidence that a shelf collapsed in a paint store. Yet these are works that have been hugely successful with both critics and the public. This must be teaching us something, but what exactly? Maybe that the formal side of a work is secondary to its meaning. I don’t know. I think those two aspects are impossible to separate cleanly.

Does it teach us that every work has its own value? I don’t agree with that either. Does it push us to value the creation process more than the finished work? Absolutely not. I think I have to give up, bask in what I’ve seen and let chaos point the way. Maybe that’s it: in total chaos the only thing you can do is stay still. An artistic representation of the eye of the storm.

It’s incredible that someone managed to achieve that with a video game, a medium built around action and interaction more than any other. Yet that’s exactly what happens. At its peak, in Vampire Survivors you stop playing. If that’s not magic, what is?

Until the next episode, ciao!