The Alters, Pirandello, and an Infinity of Mirrors

When you say “I,” which “I” do you mean? #literature #mirror #videogame

Welcome back to Artcade, the building super who waters the hibiscus by the gate, oils the lock on the front door, and calls the crew to scrape the peeling plaster off the façade near the fourth floor. If there’s time left, we’ll boot up a console and play something together. We’re all here, when will we get another chance?

One, No One and One Hundred Thousand is a long panic attack about identity. It starts with a face and a doubt. Vitangelo Moscarda’s wife tells him his nose tilts to the right, and that tiny flaw he had never noticed tears open the confidence he’d lived on up to that moment: if others see me differently, he asks, who exactly am I for them, and who am I really?

We can only know that to which we succeed in giving form. Yet what can there be in the way of knowledge? Can it be that this form is the thing itself? Yes, as much for me as for you, but not for me as it is for you; so true is this that I do not recognize myself in that form which you confer upon me, nor you yourself in that which I confer upon you; the same thing is not the same to all; and even for any one of us, it may constantly change, and in fact does constantly so change.

[…]

So you think, do you, it is only houses that are built? I am continually building myself and building you, and you are doing the same, inversely.

Pirandello puts us in front of a truth that is simple and devastating. We don’t have a single identity. We are the rough sketch composed of the gazes, nicknames, and stories that get stuck to us. Vitangelo tries to track those masks down and tear them off, except there are too many: he discovers the man his wife loves, the banker the city hates, but each character reflects back an image of him that doesn’t match his expectations.

I glanced at myself in the clothespress mirror with an irresistible self-confidence; I even winked an eye by way of signifying to that Moscarda there that we two understood each other, all the while, marvelously well. And it is but the truth I am telling you, when I say that he winked back, by way of confirming that understanding.

(You, I know, will inform me that this was due to the fact that the Moscarda in the mirror there was I; and by so doing, you will be proving to me yet one more time that you know nothing whatever about it. It was not I, I can assure you of that. This is evidenced by the fact that when, a moment later, before going out of the room, I turned my head a trifle to have a look at him in the mirror, he was already another person, even to me, with a satanic smile in his keen and brightly gleaming eyes. You would have been terrified by it, but not I; for the reason that I knew him; and I gave him a wave of the hand. He waved back at me in turn.)

Vitangelo aims for freedom by letting every mask crumble. He wants to be “no one” so he can be “anyone.” He sounds like a mystic, or like the protagonist of a video game constantly hitting respec1. Maybe he’s simply a man who stretched his vision of himself to the limits of comprehension.

If I was not for others what up to then I had believed myself to be to myself, what was I?

Luigi Pirandello (1933) [1926] One, None and a Hundred-thousand [Literature] [Novel] Project Gutenberg Australia

The Alters takes the idea of multiple identities to an even more extreme place… but let’s start at the beginning. Jan Dolski is the lone survivor of a space mission on a lost planet. He’s alone, and he has to manage a giant donut-shaped base.

Every container inside the mega-donut in space is a different room. There’s one where you grow food (screenshot below), the infirmary, the workshop, the quantum computer that knows too much, the comms room that never manages a clean connection, and so on.

As if that weren’t enough, the planet is less hospitable than a beach resort in peak season, with the only difference being that the resort is full of people (which is what makes it inhospitable), while on Jan Dolski’s planet there’s no one but a ruthless nature. In addition to radiation, lava, and other fun distractions that rival pre-dinner party games on the annoyance leaderboard, there’s also the joy of mining in inhuman conditions. Oh, and the system’s star sits a bit too close, so sunrise is lethal and the base has to be moved to stay in the shade. In short: gorgeous views, wouldn’t live there.

Soon Jan Dolski realizes Pirandello was a beginner at identity crises. To keep the base running, with the help of the know-it-all computer, Jan starts creating alternate versions of himself, each derived from a different life path he could have taken. The base turns into a dorm full of Jans who aren’t quite the same Jan. Engineer-Jan, Medic-Jan, Jan-Samurai (okay, I made that one up), and so on. To survive and complete the mission, you have to manage your own plurality.

Where One, No One and One Hundred Thousand made its protagonist suffer the versions of himself that other characters mirrored back at him, in The Alters those characters are literal reflections of the same self. They have memories, affinities, clashing egos, and across the whole adventure they take part in a kind of group therapy with a main character in trouble and copies that would prefer to be protagonists. The most important resource to manage is trust, the bottleneck is time, and the biggest risk is turning your base into a brawl among very competent people. Everyone is convinced they lived the right version of their own life. Hard to blame them.

Pirandello wasn’t writing science fiction. 11 bit studios weren’t trying to write literature. Yet something deep connects One, No One and One Hundred Thousand with The Alters. The idea that a person’s identity isn’t a well-defined object, but something variable and continuous that can change thanks to tiny shifts which, over time, turn into avalanches. Is it possible to accept that different versions can exist of something so fragile in us? Neither Vitangelo nor Jan seem to manage.

11 Bit Studios (2025) The Alters [Video game] [Survival] [19 Hours] (Xbox Series X) [PlayStation 5, Windows, Xbox Series S] 11 Bit Studios

Information Desk:

Since it’s from 1926, One, No One and One Hundred Thousand is no longer under copyright. At least in Australia.

Maybe one day we’ll end up siding with Buddhism. Because Buddhism has a theory of mind all its own, unique really. The doctrine of not-self. An idea of the self as a void. I won’t butcher centuries of human thought here; if you’re curious, start here.

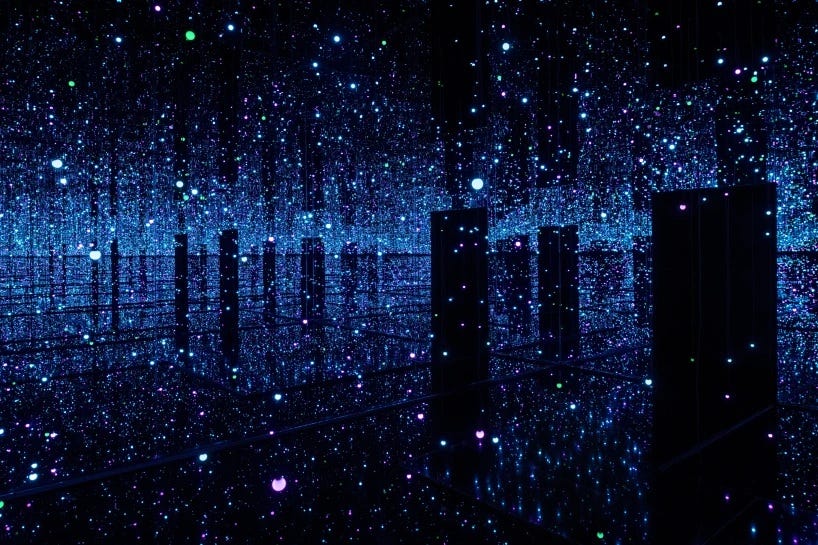

But wait, the title promised “an infinity of mirrors.” Where did they go? Was that just a nod to the countless possibilities of the self? Not just that. It was a nod to a work by Yayoi Kusama, an artist who lives (voluntarily) in a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo. Infinity Mirror Room multiplies the image of whoever walks in, which is indeed a nod to the countless possibilities of the self. It can give you a dizzy ego-trip or Pirandellian nausea; if you get the chance to step inside, tread carefully.

My last two coins

I often think about the me from ten—or even twenty—years ago. He really does feel like a different person. I agree with almost all his choices, I recognize his features, but I’m not him anymore. A while ago I watched an old family home video from a trip we all took together. Leaving aside the fact that my grandparents are gone now (which is why I stopped watching), the person, the actor, playing me in that footage isn’t me. I know it for sure, and I can’t explain why. If I took that feeling to its furthest point, every morning when I wake up I would be born again. Not a bad thought. For now, the only certainty is that Artcade will be born again in seven days. Until the next episode, ciao!

Respec is a common feature in video games: short for “re-specialization,” it lets you reset and reassign the points you’ve invested in a character across skills and attributes to give the character a different build and playstyle.