Starfield and a Poem by Robert Frost

The universe may or may not be very immense. #poetry #videogame

Welcome back to Artcade, the comfy couch-bar where we sip tea and chat about art and videogames—and, when the mood strikes, politics, sex, far-off countries, and yes, poetry. Apparently we’d forgotten that last one. So grab a seat on this virtual Central Perk sofa (Matthew Perry’s been gone a while and I’m considering another Friends re-watch—third time’s the charm) and enjoy the read!

Far star that tickles for me my sensitive plate

And fries a couple of ebon atoms white,

I don't believe I believe a thing you state.

I put no faith in the seeming facts of light.I don't believe I believe you're the last in space,

I don't believe you're anywhere near the last,

I don't believe what makes you red in the face

Is after explosion going away so fast.The universe may or may not be very immense.

As a matter of fact there are times when I am apt

To feel it close in tight against my sense

Like a caul in which I was born and still am wrapped.

Robert Frost (1947) Skeptic [Poetry]

I asked someone who knows way more about poetry than I do for a quick sketch on Robert Frost. Over to Isidora Tesic:

Robert Frost was born in San Francisco on March 26 1874 and died in Boston on January 29 1963. He spent his first eleven years in California; after his father’s death he moved back to New England with his mother and sister. He attended Dartmouth and Harvard without graduating, bounced between odd jobs, and in 1895 married Elinor White, with whom he had six children. In 1912, after their farm failed, the family relocated to England. There Frost mingled with the literary circles of the day, where he met poets such as Edward Thomas, Rupert Brooke, Robert Graves, and, above all, Ezra Pound, who championed him through the publication of A Boy’s Will and North of Boston, collections that would cement his success. Returning to the U.S. in 1915, he became one of America’s towering poets, the only one to snag four Pulitzer Prizes. His younger sister would die in a psychiatric hospital in 1929; he would lose his wife in 1938; only two daughters would outlive him; and he would struggle with depression.

To lay out the chronological gallery of events that defines a man’s biography invariably tempts one to divine, from the unfolding of those events and the choices behind them, the reasons: existential, poetic, practical; the very reason for being and for having been. In the presence of Frost, that attempt, or rather that temptation, hesitates. Atypical for his time and recalling an American poetic lineage that summons Ralph Waldo Emerson and Emily Dickinson, his poetry is transparent, clear, and this is true both in form—Frost flatly rejects free verse, and his metrical choices are varied, extending even to rhyme—and in essence. He offers the low-lying delicacy of images, the reflective, pristine dialogue of a defined lyrical self with the other-than-self. Where Nature reigns, a Nature that just is: not a function of humankind, not merely the backdrop to human life, but vibrant, interlocutory, imaginative; and humankind inhabits it with the same disposition to question it that it possesses when questioning itself, the movement running both ways. Yet the appearance of simplicity—the almost homespun narrativity—of Frost’s lines hides allusion. What seems to count in Frost is the inexhaustible (perhaps unfulfillable) desire to speak further, the remainder that lingers after what is said. “Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting,” Frost declares (but how far?). And again: “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.” Both statements point to what endures beyond the poetic act: a kind of imprecision—or rather, an illusion of precision—that is the residue of creation’s own continuation, of its potentialities; the superimposed trace of every act of creation, the yearning, the longing, for the consummation of the creative act is also, in a sense, an act of death—an ending through definition.

And it is to the lustrous transparency of Frost’s poetry that we owe the possibility of divining, of recognizing—just as beneath the thick sheet of ice lies the belly of the lake on which we are walking—the inner upheavals of his lines, the dark, compulsory mobility beneath, which interrogates him and us about life, about our very disposition toward life, about the end, about the terror of the end, and, again, about our obstinate advance in spite of.

Bethesda Game Studios (2023) Starfield [Video game] [Rpg] [21½ Hours] (Xbox Series X) [Xbox Series S] Bethesda Softworks

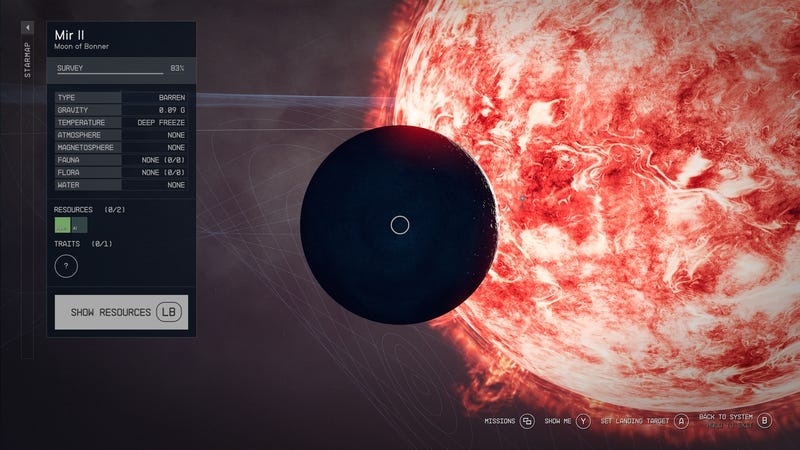

“The universe may or may not be very immense.” Starfield is a Bethesda classic: hundreds of hours if you go full completionist (the main quest is surprisingly short though); factions and counter-factions, each with its own soap opera; inventories—plural—crammed with implausible loot; shipbuilding, off-world homesteading, a sitcom’s worth of companions, and the studio’s trademark “realistic” object physics. Oh! I almost forgot: an entire cosmos politely waiting for you to solve its problems.

Information Desk

Isidora Tesic was born in Brescia in 1996. Her stories and poems have appeared in Nazione Indiana, Il Primo Amore, Nuovi Argomenti, and since 2015 she has written for Q Code Magazine.

Some players swear No Man’s Sky pulls off space exploration better: hop in, blast off, pierce the atmosphere, and cruise—no menu gymnastics required. YouTube is brimming with head-to-heads if you want the nitty-gritty.

Speaking of nitty-gritty, behold Bethesda’s legendary “toast physics.” Rule #1: steal a slice, leave it at home, come back later—it’s still there. Rule #2: fill your quarters with toast and the slices behave exactly like, well, toast. Someone even stuffed a starship with potatoes.

My last two coins

Counting stars brings its own headaches: stand too long and your neck mutinies; lie on the beach and you nod off. Around twenty-eight (or was it twenty-nine?) I always lose track and quit. And really, why count at all? For all I know, each bright dot might be hiding another star— what if I’m really looking at three, lined up in a neat row? Fine, back to counting… this time I’ll just multiply everything by three. Until the next episode, ciao!

Hello from a sympatico Substacker.