High on Life and David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest

A meeting point between two worlds light-years apart. #literature #videogame

Welcome back to Artcade—more grandpa than project. He starts one story, elbows in another, then gets lost in the… what? What were we talking about? Ah, yes: that time I started a sentence and never finished it because—well, never mind. Speaking of detours, starting today there’s a new section in the Artcade menu: World Tour. You already knew I wasn’t going to finish that sentence, right? Anyway, in World Tour you’ll find all the pieces where we explore places and cultures through video games. And now, back to today’s episode: we’re floating into something Christopher Nolan (yes, the director of “Inception”) would probably love. Enjoy the ride—the read!

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest may look like a novel; in truth it’s a solar system. We’ll zoom in on a single detail—its end-notes—because that one detail reshapes the whole book.

(For reading ease I’ll drop each note right after its cue; in the actual volume they live in a separate section tacked on after the final page).

The very first note:

He had never been so anxious for the arrival of a woman he did not want to see.

[…]

The appropriation artist had been led to believe that he was a former speed addict, intravenous addiction to methamphetamine hydrochloride1 is what he remembered telling that one, he had even described the awful taste of hydro-chloride in the addict’s mouth immediately after injection, he had researched the subject carefully.

1. Methamphetamine hydrochloride, a.k.a. crystal meth.

So far, nothing odd: a classic footnote that does exactly what footnotes usually do—explain a term. Turn a few pages, though, and a new note blows that calm to pieces:

As if the Moms’s head was some sort of overtight helmet Orin can’t wrestle his way out of. 2 In the dream, it’s understandably vital to Orin that he disengage his head from the phylacteryish bind of his mother’s disembodied head, and he cannot.

2. Orin’s never once darkened the door of any sort of therapy-professional, by the way, so his takes on his dreams are always generally pretty surface-level.

The note is no longer commentary; it’s story.

From here on, every superscript number forces the reader to choose: keep marching down the main road or veer onto a side-street with no clear exit? By note 3 you’re wading through nearly a full page; by note 5 something even more disorienting happens—something you might not notice at first glance.

[…] a traditionally smaller and harder-core set tends to rely on personal chemistry to manage E.T.A.’s special demands — dexedrine or low-volt methedrine5 before matches […]

5. Known usually as ’drines — i.e. lightweight speed: Cylert, Tenuate, a Fastin, Preludin, even sometimes Ritalin. It’s worth an N.B. that, unlike Jim Troeltsch or the Preludin-happy Bridget Boone, Michael Pemulis (out of maybe some queer sort of blue-collar street-type honor) rarely ingests any ’drines before a match, reserving them for recreation — some people are wired to find heart-pounding eye-wobbling ’drine-stimulation recreational.

a. Tenuate’s the trade name of diethylpropion hydrochloride, Marion Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, technically a prescription antiobesity agent, favored by some athletes for its mildly euphoric and resources-rallying properties w/o the tooth-grinding and hideous post-blood-spike crash that the hairier-chested ’drines like Fastin and Cylert inflict, though with a discomfitting tendency to cause post-spike ocular nystagmus. Nystagmus or no nystagmus, Tenuate’s a particular favorite of Michael Pemulis, who hoards for personal ingestion every 75-mg. white Tenuate capsule he can lay hands on, and does not sell or trade them, except sometimes to roommate Jim Troeltsch, who nags Pemulis for them and also goes into Pemulis’s special entrepôt-yachting-cap and promotes still more of them on the sly, a couple at a time, feeling that they help his sports-color-commentary loquacity, which secret promotions Pemulis knows about all too well, and is biding his time to retaliate, never you fear.

Note 5 nests a lettered sub-note. It’s not an outlier: many notes bloom into letters, transcripts, even mini-dialogues, and some of those sprout sub-notes of their own (note 324 holds six of them, a–f). Filmographies run for pages; digressions, wisecracks, clarifications—all told, the notes run to a full hundred pages and take up a major portion of the book. They’re the most far‑reaching literary example of a love of digression.

David Foster Wallace (1996) Infinite Jest [Literature] [Novel] Little, Brown Book Group.

High on Life is a first-person shooter set on an alien planet starring—you—an accidental bounty hunter. Nothing revolutionary, except for the weapons: each gun is a garrulous extraterrestrial. Every time you kill an enemy, try to shoot a civilian, or just gaze at something shiny, the gun fires off a comment.

Everybody talks here. Enemies threaten you via giant video calls, passers-by pour out their life stories and, if you walk off mid-monologue, ask—quite offended—why you’re not listening.

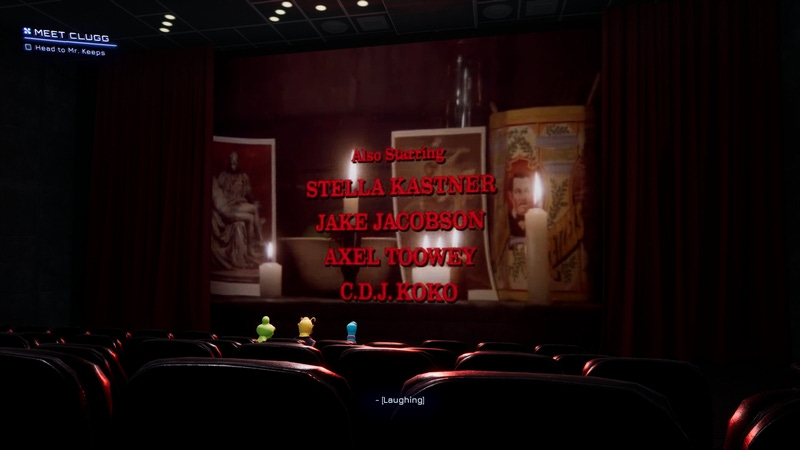

The game is filled with anecdotes, quips, and digressions. Yet all that chatter pales the moment you buy a gizmo that can teleport a cinema right onto the map. Torn from some other dimension, the Krust Theatre snaps into place.

Inside: an empty auditorium save for three patrons in the front row.

Sit down and you can watch the whole B-horror flick (1 h 38 m). But don’t think you’ll get to enjoy the movie in peace: the three viewers do nothing but comment on the film among themselves. Between quips and bursts of laughter (screenshot below), the movie‑theater experience is complete.

The first‑person shooter melts into a midnight movie. And what do those three in the front row have to say? That, too, is a true love of digression.

Squanch Games (2022) High on Life [Video game] [First Person Shooter] [9 Hours] (Xbox Series X) [Windows, Xbox One/S, Playstation 4/5] Squanch Games

Information Desk

In 1996 interview David Foster Wallace said the first draft of Infinite Jest hit 1,700 pages; roughly 500 were cut. The notes alone once filled almost 400 pages; only about a hundred made the published edition.

If you’re a fan of Rick & Morty’s motor-mouth humor, High on Life scores extra credit.

More movies hide inside High on Life: three play nonstop on the living-room TV where the game opens. Someone online described them all, or you can watch the entire Demon Wind on YouTube.

My last two coins

I like to bring distant worlds together. Since launching Artcade my favorite game has been unearthing unlikely affinities across wildly different languages—visual, thematic, stylistic, technical. Each new pairing feels like an archaeological find: a pocket-sized Rosetta Stone capable of translating media that supposedly don’t speak. That jolt of surprise—a literal body-spark, trust me—is exactly what I try to pass along, column after column. Until the next episode, ciao!